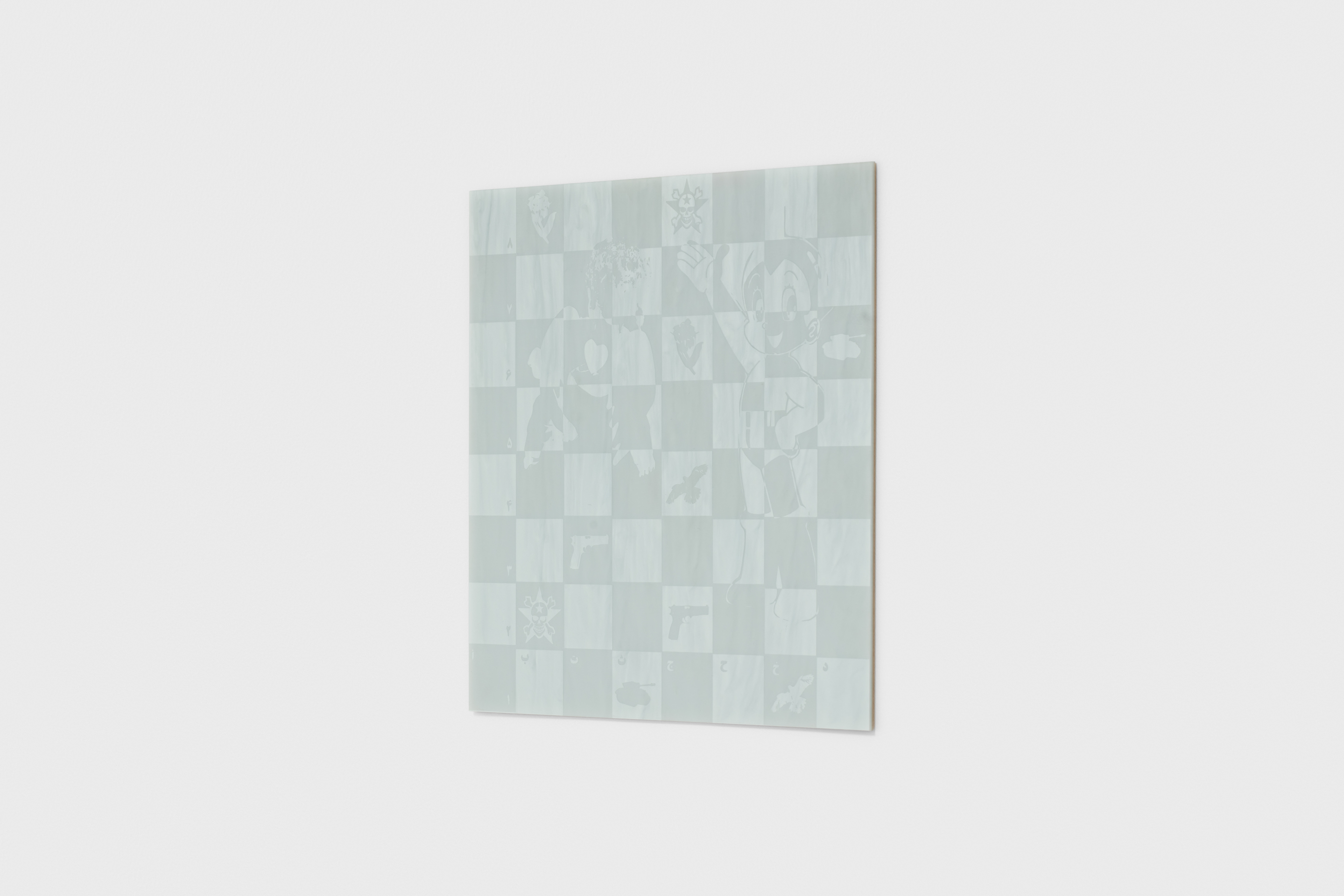

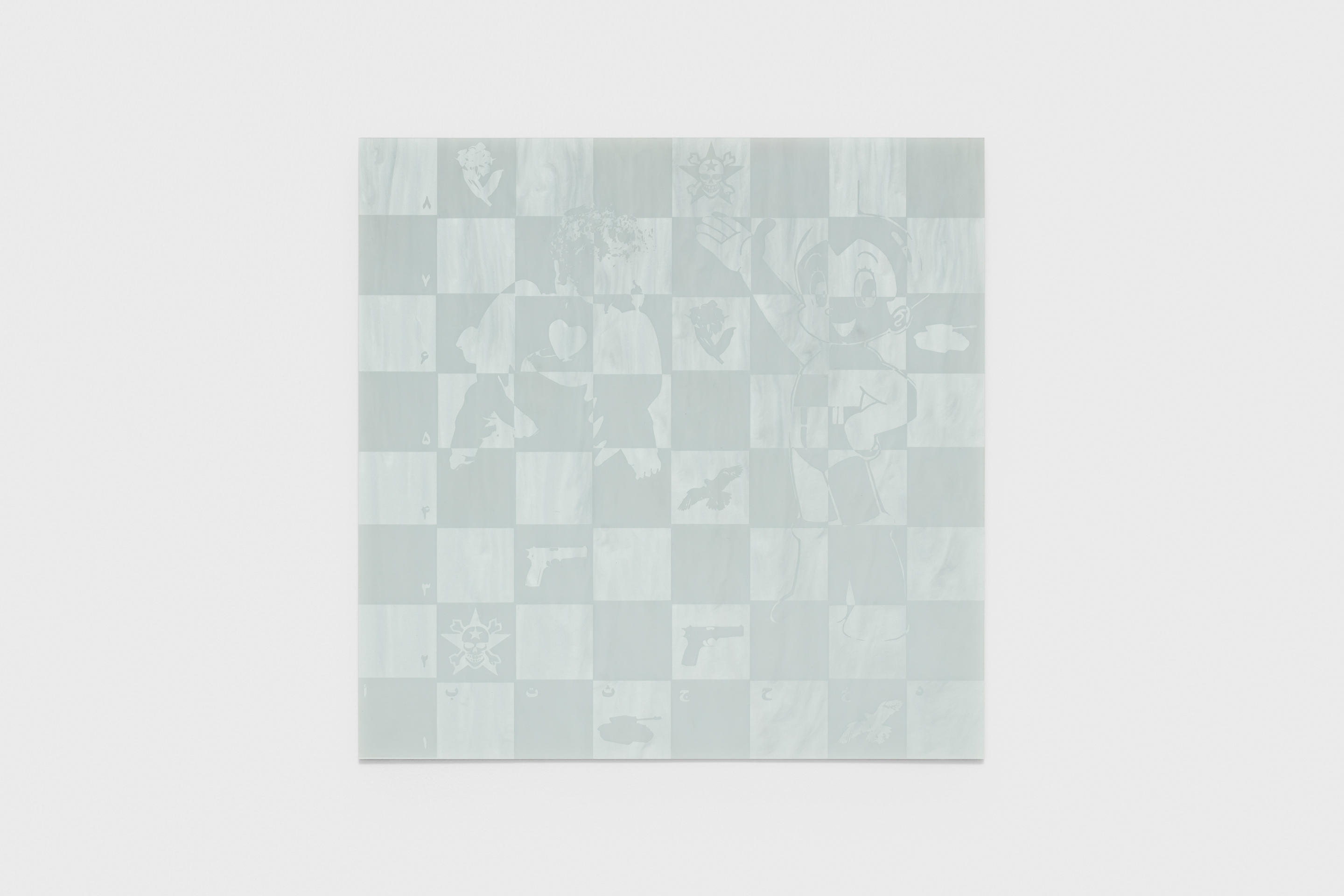

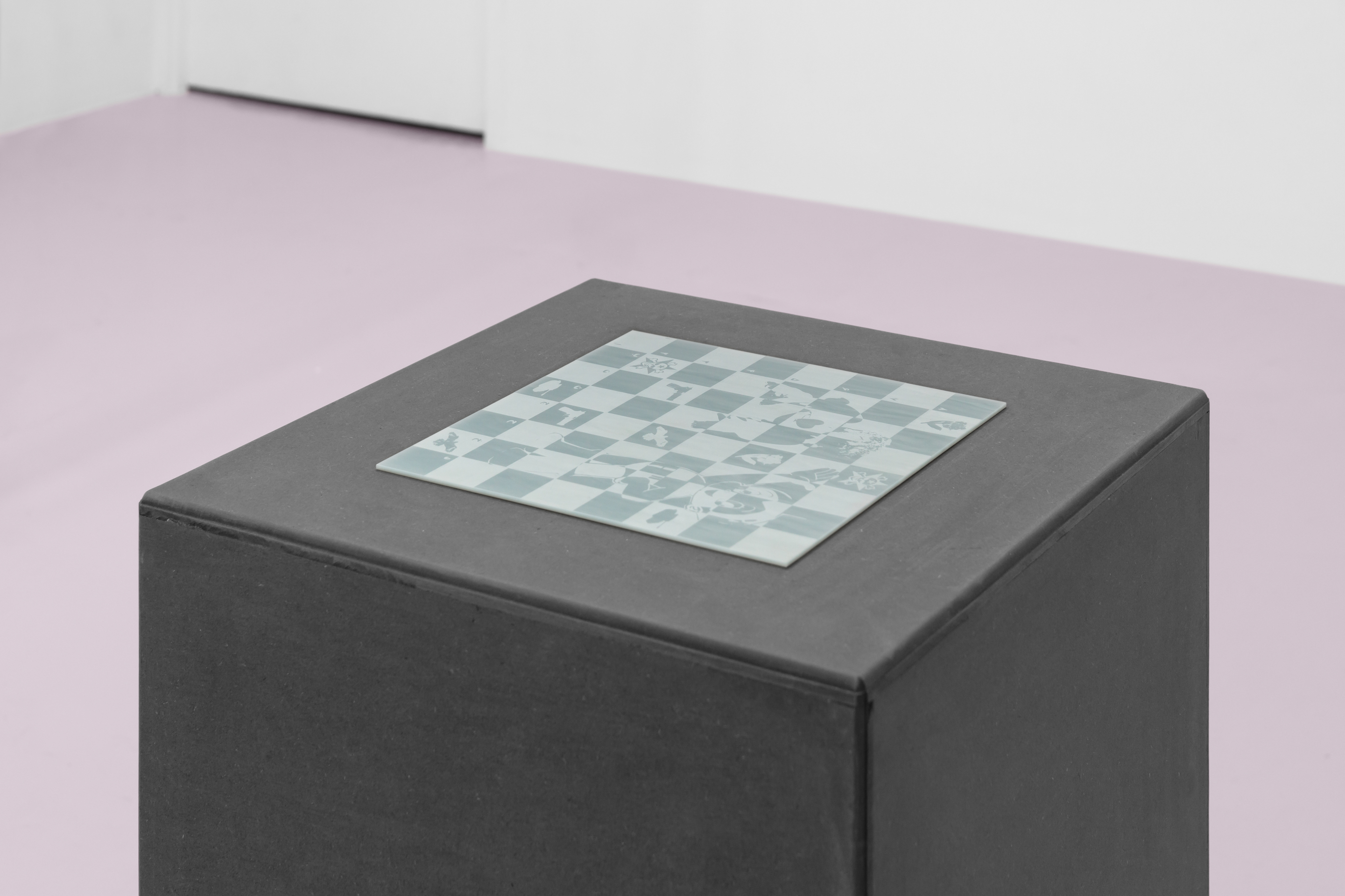

Saccharine Symbols, Rose Easton, London, UK (2023)

NOVEMBER 15TH – DECEMBER 20TH 2023

Saccharine Symbols

Works by Marisa Kriangwiwat Holmes, Shamiran Istifan, and Tasneem Sarkez

Photo by Jack Elliot Edwards

Press Release

Text by Phillipa Snow

I

There is no recorded evidence that anyone has ever hidden a razorblade inside a candied apple, per the urban legend, and yet as an image it is so conceptually perfect that the truth no longer matters–all that matters is its neat suggested marriage of the sweet and the profane, the evil sting beneath its sugar. It helps that the shade of a traditional candy apple is not merely red, but lurid, bloodlike; that when held in the hand it faintly resembles, in its size and in the pseudo-wetness of its gloss, a human heart. A red apple was the weapon of choice for the evil Queen in Snow White, whose exaggerated, draggy gorgeousness–like that of a piece of fruit with a blade concealed within it–camouflaged her cruelty, and in the 1937 Disney adaptation of the story, we are shown her admiring the apple’s loveliness and colour even though she has just covered it with poison. Even knowing that something beautiful may kill us is not necessarily enough to stop us wanting it, as fools and aesthetes alike have learned to their detriment for centuries, perhaps millennia. In fact, rather than outright death, the apple puts Snow White into what

is described as “a sleeping death,” and this feels like an appropriate reaction to a dangerous but desirable object–a drugging, a relinquishment, a kind of freezing of one’s faculties that carries on until an outside party shows up to eject us from the trance.

II

Love itself is a little like an apple with a razorblade inside it, making it logical that one Courtney Michelle Harrison, the daughter of a psychotherapist and a road manager for the Grateful Dead, decided to adopt “Love” as a pseu- donymous surname in the early ‘90s. She had already displayed a flair for smuggling darkness, Trojan-Horse- style, into the nominally saccharine and safe, as when she had auditioned at eleven for the Mickey Mouse Club, and had chosen to read Sylvia Plath’s poem Daddy as her monologue. (“Daddy, Daddy, you bastard, I’m through.”) Her knack for using ultrafeminine signifiers for perver- sion and subversion would go on to become not only one of the defining aesthetic characteristics of her band, Hole, but one of the defining characteristics of rebellious modern girlhood. While it would no doubt be frowned upon to refer to a fashion trend as “kinderwhore” circa now, it is undeniable that the influence of the look she helped to popularise–babydoll dresses, white tights, disarray–lives on through a contemporary fondness for combining bimbodom and radicality among Very Online feminists. The idea was not to “look like the innocent flower / But be the serpent under’t” per Lady Macbeth, but to approximate a style that was both flower and serpent: cute and mean, sick and soft, using “fuck me” to hide (or not quite successfully hide) “fuck off.” It might be argued that this tension is a visual representation

of the tightrope walk of femininity itself, in the same way that it might be argued that the murderous apple is an ideal metaphor for the risk inherent in romance.

III

Some flowers, at any rate, are not all that innocent

in the first place: the real, historical Macbeth is said

to have used deadly nightshade, crushed into wine,

to do away with his Danish foes. The scientific name for deadly nightshade is Atropa Belladona, derived from the name of the mythological fate Atropos, and the Italian for “beautiful woman,” as if a bloom that killed and a total babe were one and the same thing. Even roses, as the terminally unhip song reminds us, have their thorns–although when they’re sold as sweet romantic tokens, they are stripped of them in order

to prevent an injury to the lover who receives them. Strange, since the breadth of human experience, and thus of human relationships, requires from us the ability to tolerate pain as well as pleasure, and one might argue that without an invigorating injection of the latter, the former lacks real bite.

IV

The fact that the poison cyanide smells like almonds

is a detail that has appeared in a number of detective stories, and for this reason, it is tempting to imagine it might also taste like, for example, marzipan. The mystery of cyanide’s taste was finally solved in 2006, when

an Indian man took his own life and, with remarkable prescience, described its flavour as he died: “Doctors,” he wrote, “potassium cyanide. I have tasted it. It burns

the tongue and tastes acrid.” It surprised me to learn that the late man was a goldsmith, and not a scientist or a writer or, perhaps, an artist–something about the desire to document this experience suggested both

a thirst for knowledge, and an innate flair for poetry. Still, with all due respect to the dead, it is a little disappointing to learn that cyanide tastes like poison, and not like the pastel-coloured Jordan almonds I was picturing before I read his note.

The idea of cloaking something violent in something more saccharine intrigues, and sometimes thrills, precisely because the combination’s ability to trick the viewer–or the consumer–can be used both favoura- bly and cruelly. As an abstract tool, it can be utilised for political and social gain: a means of seducing the unwitting subject into letting down their guard just long enough to make them digest something less palatable than they had expected. It can be weaponised for good as well as evil, and if being thus fooled is not exactly pleasant, it certainly teaches us a lesson. One of my earliest memories is that of eating a candied apple, when I was still small enough that I must have been biting into it with milk teeth. I remember that the toffee shattered; I remember that it cut the inside of my mouth, so that with the sugar and the pulp, I tasted blood–rich, metallic, sharp, a formative inkling of the fact that hurt could hide in something sweet.

Marisa Kriangwiwat Holmes (b. 1991, Hong Kong), lives and works in New York. She received her BFA from ECUAD, Vancouver in 2017. Holmes’ digital collages are composed in a melodic manner, with a media-exhausted audience in mind. Recent solo and two-person exhibi- tions include A Broad Private Wink, Nicelle Beauchene, New York (2023); Infinity Ball, Unit 17, Vancouver (2022); My Owns, Project Native Informant, Online (2021); Everything Leaks, Polygon Gallery, Vancouver (2020); Open Heart Run Off, Sibling, Toronto (2019); Keep Your Eyes On Your Prizes, Calaboose, Montreal (2018) and ddmmyyy, Artspeak, Vancouver (2018). Select group exhibitions have been held at the National Gallery of Canada (2022); Royal Academy Antwerp, Access Gallery & Centre A, Vancouver (all 2017). Holmes was the winner of the second annual Lind Prize in 2017 and in 2022 she received the New Generation Photography Award from the National Gallery of Canada.

Shamiran Istifan (b. 1987, Baden, Switzerland) lives and works in Zurich. Istifan’s art practice focuses

on layered social dynamics, motivated by her personal experience of the way class, gender and religion shape collectivism, politics and personal relationships. Through an intimate aesthetic her work points to the way symbolism permeates daily life. Recent solo exhi- bitions include: Precious Pipeline, Rose Easton, London (2022); Law&Order, Kulturfolger, Zurich, Switzerland (2021); G by Destiny, All Stars, Lausanne, Switzerland (2021) and Micro Entities, Material, Zurich, Switzerland (2020). Selected group exhibitions include: In the Green Escape of my Palace, Studio Chapple, London (2022); Swiss Art Awards, Messe Basel, Basel (2022); Reflection is the Daughter of the Scandal, Angela Mewes,

Berlin (2021); As We Gaze Upon Her, Warehouse421, Abu Dhabi (2021); Depuis des Lunes, Urgent Paradise, Lausanne (2021); 5th Floor, Centre d’Art Contemporain, Geneva (2021) and Nour el Ain, Karma International, Zurich (2021). In September 2021, she was awarded the Werkshau Prize by Kanton of Zurich for her work Ex Amore Vita: Ladies’ Room, 2021.

Tasneem Sarkez (b. 2002, Portland, USA), lives and works in New York. She is currently completing her BFA at NYU and will graduate in 2024. Sarkez’ practice considers ways of identification, collecting, archiving, and finding refuge in cultural materiality and proximity to it. Through extensive research, and the creation of her own archive, Sarkez works to develop her own translational abstraction of Arabness. Selected exhibi- tions include: Me and you and me and, SADE Gallery, Los Angeles, US (2023); Beginner’s Luck, Rosenberg Gallery, New York (2023); Transversal: Where We Come From and Where We Are Going, 80 WSE Gallery,

New York (2023); Printing the Future, Diefirma Gallery, New York (2022) and Liminal Space, curated by Annabelle Park, 42 Rivington Street, New York (2021). In 2023 she received the Martin Wong Award from the Martin Wong Foundation. Her work is in the collection of the Thomas J. Watson Library in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

For general and sales enquiries,

info@roseeaston.com

For press enquiries, fabian@strobellall.com

Rose Easton

223 Cambridge Heath Road London E2 0EL

+44 (0)20 4529 6393 @roseeaston223 www.roseeaston.com

For press enquiries, fabian@strobellall.com

Rose Easton

223 Cambridge Heath Road London E2 0EL

+44 (0)20 4529 6393 @roseeaston223 www.roseeaston.com